Delayed adolescence, halfway-sadness, and collectively loving

The Beths

Words: Saraphina Forman

March 5, 2023

On February 28th, I went to see The Beths perform at The Sinclair in Cambridge. It was a good call. If you don’t know The Beths, they’re an indie rock band from New Zealand. The band consists of Elizabeth Stokes, Jonathan Pearce, Benjamin Sinclair (unrelated to the venue’s name!), and Tristan Deck. The Beths have roots in the alternative music scene of Auckland, DIY, which is flourishing by necessity because of the country’s relative isolation and small population. Because of the lovely politics of the country, an incubating The Beths were fed by a grant New Zealand gives to 30 artists every two months, which, as Stokes told Performer Magazine, was a “good way to feel motivated and get some support” as they were developing. Now with three full-length albums under their belt, their music is called “uptempo lyrically existential heavy-riff, harmonic garage-rock style.”

There’s a beauty to being a fan. On the train to the concert, I was looking forward to immersing myself in the crowd. It’s less about passivity and more about being part of a radical collective, loosening the grip of hyper-individualistic culture for a moment.

![]()

The night I went to see them, it was a rainy Tuesday, and the space filled up slowly, fans milling and chatting about as we waited for the concert to start. I heard someone behind me say, “The crowd is older and more male than I expected.” This was true, but that always seems to happen at The Sinclair. That night, the audience may be best described as sets of dads and their they/them children. There was a bit of a generational slope to the audience. Towards the back, there were bald, bearded men with glasses and baseball caps wearing those lined jackets in the liminal space between coats and flannel shirts. As I moved to the front of the crowd, there were an increasing number of patterned, colorful button-downs. Mustaches and long curly manes and pastel-dyed pixie cuts. Jumpsuits and layered T-shirts and tattoos. Orange and navy beanies were peppered throughout.

One of my favorite things about The Sinclair is that they often curate shows where the opener doesn’t feel like an opener at all. Actually, when my friends asked what concert I was going to, none of them had heard of The Beths, the main act, but were fans of the opener, Sidney Gish. (Maybe it’s a New Zealand thing? Anyway…) Gish’s set was a good time. In her words, “it was chill laid back Tuesday night vibes.”

Gish went to Northeastern University, and seemed to connect with the college-populated audience, as someone who makes references to being “a depressed chick in a frat party.” Sidney Gish offered advice on college in general: “Anybody here go to college? [Yeahhhh] Sometimes it’s something you gotta do. I did that once. I’m still capitalizing on the things I felt there. Mainly sadness.” At the end, she wished us good luck on the midterms that audience members had shouted out they had when she asked how our days were.

Gish kicked off the concert with a cover of STRFKR’s “Rawnald Gregory Erickson the Second.” She then composed a series of intricate loops for her songs for sometimes minutes at a time. She was humble about it (“take a minute and have a conversation with whoever you’re standing next to while I build up this song”) but it was incredible to witness the skill in action as she recorded melodies skimming over the high register, surging arpeggios, brassy, accented strumming patterns and bass-filtered lines on a looper pedal before stamping on the drums button and singing her hyperspecific, dry lyrics. The crowd especially enjoyed songs like “Sin Triangle,” and “Presumably Dead Arm.” She ended the set with her latest single, “Filming School.” She sang many of these with a more energetic, spunky tone than the studio recordings, and some of them, like “I Eat Salads Now” in a higher key too. Gish expressed fears resonant to the Gen Z ethos, such as inevitable participation in capitalism and general exhaustion: in the crescendo of “Presumably Dead Arm,” Gish predicts a bleak future where she’s “married to personified business casual khakis.”

Gish touched on a theme of delayed adolescence that The Beths later expounded on, by mentioning a “14th-grade prom” in one of her songs. Many of this angst is old youthful recklessness ("We're gonna go to a show, And then come home and then probably die”) but takes on a different air given the hyper-contemporary references elsewhere, such as the Uber driver in the line just before.

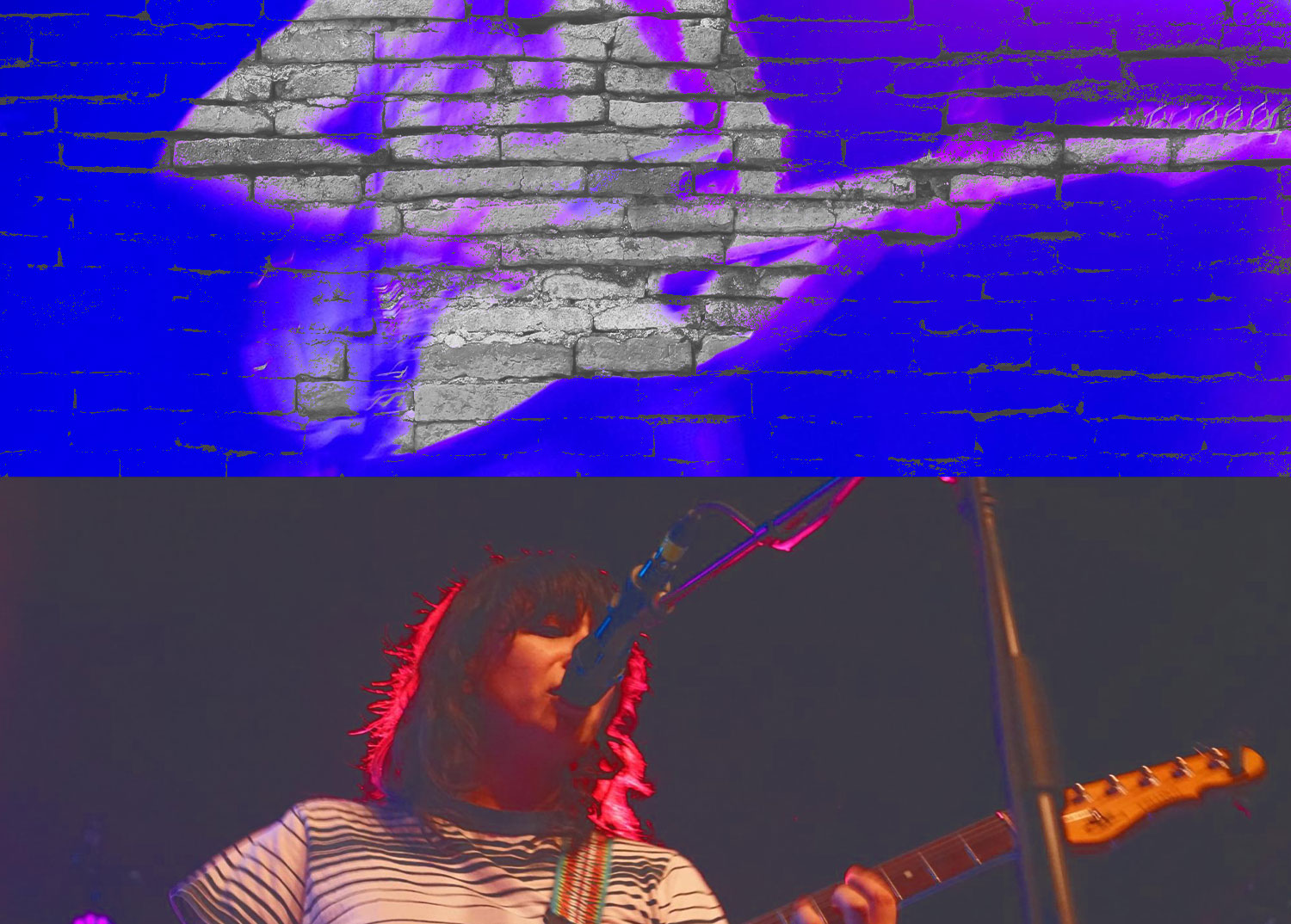

Then, The Beths came on. They crashed in with a powerful “Future Me Hates Me,” the lead single off of the likewise-named album from 2018. They greeted the crowd: “What a beautiful Tuesday,” and then the crowd-pleasing follow-up: “Did you know that in New Zealand it’s Wednesday?” Their setlist was peppered with songs from their 2022 album Expert In A Dying Field, as well as older fan favorites. The whole production was like a complicated dance. In the midst of tempo changes, mutating riffs, and tongue-twisters worth of lyrics, Stokes would hit the pedals so much it was like she was trying to stamp out fire. A particularly cool effect was the fractured guitar in “Best Left.” Stokes’ black G&L Tribute Fallout guitar and Pearces’ Goldtop ’78 Les Paul Deluxe guitar were in communion, not with a clear sanctioning or delegation of the “rhythm” guitar but rather playing off each other in pinging melodies. Pearce had some killer guitar solos as well, a combination of straight-up technical chops exhibited in a fluttering staccato picking hand and a slithering, bending right hand. He pressed into the high notes while gracefully staggering around the stage. Particular highlights were the legato “Whatever” solo and the solo of the encore’s “I’m Not Getting Excited.”

![]()

The band established a warm rapport from the get-go. There was a big, inflated (or stuffed??) half of a fish displayed vertically onstage as per their latest album cover, as if emerging from the stage and swimming up into the smoky lights above, yellow eyes staring into the audience–but in a friendly way. At one point, they challenged the audience to come up with a name for it. Pearce praised us when we finally came up with “Sidney Fish” (Sidney Gish’s long-lost cousin, perhaps). In another interlude, the bassist, Benjamin Sinclair made an extended plug for his tour blog, “Breakfast and Travel Updates.” They invited any crowd members to follow it “if you need stability in life,” because Sinclair posts every day, or to email breakfastandtravelipdates@breakfastandtravelupdates.com if you just need “life advice.”

Given the audacious lyrics of some of The Beths’ songs, I was surprised by how modest and almost shy Stokes was. She came in with a white dining hall-esque mug from which she sipped throughout, and seemed to embody that personality, if not for her unflinchingly honest vocals and roaring guitar. Her stage presence was humble and friendly, but stunningly intense, closing her eyes in stillness as she traversed the octave and emotional ranges of her songs. In an era when alleged authenticity is fetishized, the lack of naturalness in the stage presence only added to the experience. Much like with the self-proclaimed “nerdy” way they approach music, Stokes was transparent and friendly on stage, at one point chastising herself for going through her interlude “bits'' too early on: “You really need to save some of your bits for later in the set. Take my advice.”

The vocals sat quite quiet in the mix, which was a bit disappointing at times, but also only seemed to add to the experience at other times, putting more emphasis on the collectivity rather than a single narrator. The band resisted this hierarchical tendency.

In the midst of the more punk-oriented sound, songs like “You Are A Beam of Light” stood out, a soft fingerstyle reflection amongst the slew of heavier rock songs. Stokes’ right thumb on the low E string set a constant pulse for the song, as her other fingers rippled through transforming chords with a skill that called to mind her classical training. The vocals were more audible without all the noise, and the harmonies took center stage in all their glory. The richness of the vocals, even without the strums and drums, fleshed out the song into a full-bodied, thrumming piece. “You Are A Beam of Light,” from their 2020 album Jump Rope Gazers was The Beths’ “first attempt at an ‘acoustic’ song,” as Stokes humbly framed it–but the palpable chills amongst audience members calls this novice narrative into question (DIY Mag). Although this song still has The Beths’ determinedly optimistic tint (“You are a beam of light, Maybe that’s why your battery runs dry”), this time it feels more like a desperate attempt to justify the painful suffering of a friend–a positive tone for survival’s sake, bearing a melancholy perfume that can be ignored but not completely filtered away. The lyrics felt post-apocalyptically intimate, or rather, contemporary:

There are some angsty, reckless lyrics (“I will go out tonight, I’m gonna drink the whole town dry, put poison in my wine, and hope that you’re the one who dies” or “I wanna crash the car and hit the water” or “You wouldn’t like me if you knew what was inside of me”).

These lyrics sound sort of “teenage,” actually, which was why I was surprised the band members were over a decade past their teenage years. But there is a reason for this. When The Beths’ were beginning to write much of their core content, Stokes had just broken up with her partner of eight years–which means it was a relationship that had started in her teens and lasted into when she was a twenty-something. Then recently during the COVID lockdowns, Stokes revisited this: “needed something to kick me into gear…I felt numb to what was happening around me. So I began digging through old journals, tapping back into old emotions. That means some of these songs are very ‘2021’ and some of these songs place me in 2015, emotionally” (Relix). Their latest album, Expert In A Dying Field references this “second adolescence” of warped time: As Stokes states in her title track, “Love is learned over time, ’til you’re an expert in a dying field.” Thus, The Beths was formed in the aftermath of a breakup which was causing Stokes go through “a second adolescence, on my own for really the first time” (Relix). The “adult break-up album” sometimes gets a bad reputation, but The Beths do it well (The Flood).

Although the music may have “adolescent qualities,” the beauty of second adolescence is that it inevitably does give more perspective. The fact that The Beths is a bit of an older band–early 30s, but still older sibling vibes compared to the “sexy babies” that populate a lot of the contemporary music scene today–does influence the music. The fast, pop punk songs with sad lyrics that have become increasingly popular recently (e.g. Olivia Rodrigo) but with a harder, more instrumental spin. But also another layer of contrast–if you peel away the upbeat sound and the sad “meaning” beneath that, there is actually a core of optimism and good-natured selflessness. They don’t get carried away with sadness in the way where it becomes extreme self-absorption, victimhood, or self-fetishization into an aesthetic, or even self awareness to the point of cynical paralysis.

Their songs reflect their maturity and growth. As Pearce said in an interview, “There’s only so many times you can write that fast, self-loathing banger…How many of those are in the back catalog now? It’s like, OK, we’ve gotta find some other emotions to put into the music. [Like] love songs that say ‘I love you’, without also saying ‘but I hate myself.’” I don't add The Beths to my “sad” and “happy” playlists that somewhat toxicly draw me deeper to these extreme emotions. Rather, I can experience fullness in most any single The Beths song.

The Beths feel emotions, but they feel a full range of them, even within one moment. There is this concentration situated within the broader context. Rolling Stone’s assessment of The Beths as “self deprecating power pop” seems derogatory. But I love this self deprecation because it's so decidedly not a self-flagellation that prevents growth. It talks about feeling bad but in a human way, not in a pathological or narcissistic way (making the world drop at their feet because oh they suffer the most) not overly making it all about them. Stokes sings about her emotions matter of factly–expressing their intensity without losing sight of the broader world. Listening to The Beths feels like processing emotions vicariously in a healthy way, like eating a delicious plate of spinach. There’s also something about watching The Beths that’s a bit comforting, like a cool older sibling, or a more mature version of myself. Someone who might still hate me at times but who hates me a bit less. And often, that can honestly feel like the best case scenario.

Stokes is a wonderful lyricist, and there are plenty of words on the album, but they’re the type of band where you don’t have to hang onto every word. It feels like there’s not that intuition, and it's not instinctual.

The way I find myself listening to most of The Beths lyrics is letting the words wash over me in a delicious tumble of New Zealand-intoned syllables, where certain words or phrases catch on if their meaning is magnetic to me. “Future Me Hates Me” is one great example–it initially stuck to me because I (somewhat stupidly??) pictured a milkshake where Stokes said “cold shakes'' and latched onto that without understanding much.

The literary arts major in me (sorry) couldn’t help but appreciate how some of the song titles are also somewhat perplexing diptychs of words like “Best Left” where you can’t immediately piece together what the subject-object combination is or delineate what's the noun, so they become somewhat solid formal objects. The lyrics wash over me in a delicious tumble of New Zealand-intoned syllables. Not all of the meaning is immediately apparent, nor is it riddled with intense pop culture references that a lot of today’s indie music is. It's metaphorical at times, but also beautifully literal. It feels like a choose your own adventure experience listening to it–there’s just so much going on. In the best of ways. It doesn’t feel overwhelming, it feels spacious enough, like I've walked into a bountiful pantry and can sit on the countertop eating whatever I desire, letting my eyes roam over the fruits, carving out a space for myself within it all. And by the end of the three minutes (their songs are pretty tight) it always feels like a full course, no matter what I was munching down on.

The Beths’ songs lend themselves to relating in many ways. For example, Stokes says “Future Me Hates Me” was about the ultimately excited anxiety of leaping into things that you think future you might regret. Stokes says the song is “not about future you looking back and hating you–it’s about present you being worried about what’s gonna happen down the road…I don’t think of it as being pessimistic. I think of that song as being an optimistic song” (Since I Left You). But in high school, I understood the song as a purely hateful anthem where a future version of myself will always unequivocally hate those past versions, such as my aversion to my old identities and the people from my town who I didn’t feel understood by and was eager to leave. A very “adolescent” reading, to be sure, but now I can appreciate it from a different way. This second adolescence inevitably comes with the nuanced perspective of more experience–it’s not a repetition but rather a reprise. And if Stokes truly is singing this as a future self looking back at the old Liz and hating her, she’s doing it while grinning–a sympathetic laugh while shaking your head.

Just as the content was dealing with seemingly adolescent feelings in a nuanced way, The Beths’ sound also reflects this callback. The music is a bit more of a traditional brand of rock, displaying a “Hey, look at this interesting thing I can do with my guitar” technical prowess, not “cool” songs, not trying to be “trendy” but more a “studied” perspective. The Beths have yet to go viral on TikTok; there isn’t really that TikTok cue point in a lot of songs. People aren’t commenting on their youtube videos things like: “it’s at 2:14, thank me later,” and you don't have to scrub backwards over and over in the songs to get to that one sweet spot. The songs are more generous than that TikTok crux. The dopamine release is distributed a bit more evenly throughout the song. The Beths showcase the music without the influencer aesthetic package. Ignoring the trends, not even in a self consciously subversive way but an authentic way.

It’s fitting, then, that in an interview, The Beths mentioned a game they play to pass time on the road which demonstrates this tendency to appreciate slowness, called “baker's dozen,” where they listen to a song thirteen times in a row.

The Beths are unabashed in the way their music isn’t necessarily what’s cool or trendy or current right now. In an interview, Stokes said, “I call us a guitar-rock band because I think it’s quite funny—sometimes it feels like period music… But it’s a palate that we just love. I don’t feel hemmed in by rock-and-roll. We could make whatever music we wanted to, but this is what we enjoy.” Their songs are tight, and usually have a guitar solo following the third chorus. But come on now! Who doesn’t love a guitar solo following the third chorus? The Beths’ adherence to their own certain formula points towards developing something to the fullest. Adherence to musical conventions doesn’t mean they're not complicated or amazing, just like something that doesn’t fit the tradition is automatically of higher value. Stokes and Pearce knew each other from high school and the band formed at music school where they studied jazz, Stokes–trumpet, and Pearce–piano. Stokes “loved learning about music, but I missed lyrics… I was communicating in melody and improvisation, learning a lot of repertoire. I was missing songs, and being able to express myself that way. I was nostalgically missing the guitar music that I grew up on. I was like, ‘I’m going to start a rock band.’ Maybe Jonathan was a little more dissatisfied with studying.”

But they still apply the “discipline” of studying to rock-and-roll. “Liz and I really connect over rejecting the ego of alternative music where people are trying to do clever things, or cerebral things. I think Liz and I look for the things that work. The devices that really get the job done and get the heart racing and make the climactic moments happen.” Their studying of musical devices definitely shows. I was uncontrollably wrought with jolts and closed eyes as their syncopated vocals and changing tempos hit hard among the cascading four-part harmonies.

Because The Beths’ music is not as much fixated on the current trend but subscribing to a varied and nuanced multiplicity both instrumentally and lyrically, everyone at the concert, dads and they/thems alike, seemed to resonate. Just like the collective musical elements in The Beths’ music, the concert experience was a collective one as well. This led to a concert that felt like a collective experience with an actively shared camaraderie, in contrast to some of the big-venued, aggressively hyped and ultimately alienating concerts that I’ve experienced.

This crowd was by far the friendliest of any concert I’ve gone to. It matched The Beths’ utter genuineness; even though we were grimacing and yelling along in passion, we took turns at who got to be gripping the stage. The girl next to me sang to the band with a beautiful desperation that made me smile. Other fans included a trio of barista coworkers who were sharing (positive) opinions on the new hire, who were bonding with a birdwatching girl who worked on a farm lamenting the fact that they all had to get up early. Another conversation nearby was intergenerational, discussing the gentrification of Cambridge and Somerville over the past decades.

The crowd gelled throughout. We were jumping for the dreamy “Jump Rope Gazers,” and got especially excited for one of the encore songs, “I’m Not Getting Excited” as the suspenseful eighth notes fizzed into a crescendo. And as Sinclair referenced in his blogpost, someone held up a Zippo lighter for the slower fingerstyle “You Are a Beam of Light.” In the song “Whatever,” the collective rumbling chant of the audience shouting the background “whatever yeah, whatever!” drowning out the backing vocals of the real band, but not in an obnoxious performative way, but rather a call and response way with the band. The angst was palpable, and it felt like real interplay. In the crackling Little Death, there was a dynamic interplay between performer and audience where the crowd shouted “YOU SAID, YOU SAID,” and “I’D DIE, I’D DIE.” I enjoyed how this added to the syncopation, emphasizing the words in a different way than you can get from any by definition static studio recording. It felt like a new thing we were creating. This felt especially true in songs like “Silence Is Golden” when the audience chanted the namesake phrase several times–we created a huge song together but also a stillness within it. (Were we singing in a New Zealand accent? I don’t know…)

![]()

The sense of a warm collective is important to the band. Elizabeth Stokes, the band's frontwoman, once said they were influenced by “band[s] like Wilco where you see how much the fans love being Wilco fans”. Stokes added, “we’re playing to the cheap seats. We’re a live band, playing rock instruments. We wanna be direct.” This is another thing the sonic elements are responsible for, because this fan relationship isn’t always the case. The Beths are a big contrast to recent notorious viral concerts such as Steve Lacy or Ice Spice where people vie for the best spot at concerts only to know one line of the songs.

The power of participatory art in the live concert felt inspiring to me in the context of the social movements and revolutionary battles we face today. “Doing” rather than consuming culture is an important part of identity and social movements, and I think I feel that at events like live concerts in venues like The Sinclair where we can come together. As Amilcar Cabral said, culture by definition lends itself to action, as culture is “vigorous manifestation on the ideological… plane.”

Most collective identities are relationships rather than stable traits. Collective identity hinges on communication which is a kind of “joint action”; this communication forms the community (Taiwo 40). As theorist Olufemi Taiwo says, “we have to share to communicate” (Taiwo 40). Collective identity is a contribution toward a “we.” Reciprocity is key. Emotion rather than information is a key part of collective identity. Melucci points out that “there is no cognition without feeling and no meaning without emotion.” After all, we say collective body for a reason!

Like most collective experiences, this one had enduring effects. By the end of it, group photos were taken of people who had been standing near each other, names exchanged, and group chats were formed between girls from various colleges in New England who’d traveled alone to see the band.

A couple of weeks ago, I turned twenty and kissed my teenage years goodbye. I’m not reluctant to leave my adolescence or yearning to remain stagnant in time. But I’m not dying to get older and over it, either. I don’t think adolescence is bad and don’t believe in the idea of constant capitalist-informed cult of self-improvement (New Year's resolutions, career ladders, and abandoning innocence for a crutch of justifying complicity with a jaded, cynical air of “I know how it really is''). At the end of the day, adolescence is a construct, and I’m flowing through what I'm flowing through; there is no right trajectory in this nonlinear existence.

The next morning, even though I walked up from the train station in last night’s clothes, smudged makeup, and very little sleep, arriving at Memorial Hill just in time for studio, future me didn’t hate me for it.

Tap into the collective experience of the concert by listening to a Spotify playlist of the setlist from the concert:

Photography by Saraphina Forman

The night I went to see them, it was a rainy Tuesday, and the space filled up slowly, fans milling and chatting about as we waited for the concert to start. I heard someone behind me say, “The crowd is older and more male than I expected.” This was true, but that always seems to happen at The Sinclair. That night, the audience may be best described as sets of dads and their they/them children. There was a bit of a generational slope to the audience. Towards the back, there were bald, bearded men with glasses and baseball caps wearing those lined jackets in the liminal space between coats and flannel shirts. As I moved to the front of the crowd, there were an increasing number of patterned, colorful button-downs. Mustaches and long curly manes and pastel-dyed pixie cuts. Jumpsuits and layered T-shirts and tattoos. Orange and navy beanies were peppered throughout.

One of my favorite things about The Sinclair is that they often curate shows where the opener doesn’t feel like an opener at all. Actually, when my friends asked what concert I was going to, none of them had heard of The Beths, the main act, but were fans of the opener, Sidney Gish. (Maybe it’s a New Zealand thing? Anyway…) Gish’s set was a good time. In her words, “it was chill laid back Tuesday night vibes.”

Gish went to Northeastern University, and seemed to connect with the college-populated audience, as someone who makes references to being “a depressed chick in a frat party.” Sidney Gish offered advice on college in general: “Anybody here go to college? [Yeahhhh] Sometimes it’s something you gotta do. I did that once. I’m still capitalizing on the things I felt there. Mainly sadness.” At the end, she wished us good luck on the midterms that audience members had shouted out they had when she asked how our days were.

Gish kicked off the concert with a cover of STRFKR’s “Rawnald Gregory Erickson the Second.” She then composed a series of intricate loops for her songs for sometimes minutes at a time. She was humble about it (“take a minute and have a conversation with whoever you’re standing next to while I build up this song”) but it was incredible to witness the skill in action as she recorded melodies skimming over the high register, surging arpeggios, brassy, accented strumming patterns and bass-filtered lines on a looper pedal before stamping on the drums button and singing her hyperspecific, dry lyrics. The crowd especially enjoyed songs like “Sin Triangle,” and “Presumably Dead Arm.” She ended the set with her latest single, “Filming School.” She sang many of these with a more energetic, spunky tone than the studio recordings, and some of them, like “I Eat Salads Now” in a higher key too. Gish expressed fears resonant to the Gen Z ethos, such as inevitable participation in capitalism and general exhaustion: in the crescendo of “Presumably Dead Arm,” Gish predicts a bleak future where she’s “married to personified business casual khakis.”

Gish touched on a theme of delayed adolescence that The Beths later expounded on, by mentioning a “14th-grade prom” in one of her songs. Many of this angst is old youthful recklessness ("We're gonna go to a show, And then come home and then probably die”) but takes on a different air given the hyper-contemporary references elsewhere, such as the Uber driver in the line just before.

Then, The Beths came on. They crashed in with a powerful “Future Me Hates Me,” the lead single off of the likewise-named album from 2018. They greeted the crowd: “What a beautiful Tuesday,” and then the crowd-pleasing follow-up: “Did you know that in New Zealand it’s Wednesday?” Their setlist was peppered with songs from their 2022 album Expert In A Dying Field, as well as older fan favorites. The whole production was like a complicated dance. In the midst of tempo changes, mutating riffs, and tongue-twisters worth of lyrics, Stokes would hit the pedals so much it was like she was trying to stamp out fire. A particularly cool effect was the fractured guitar in “Best Left.” Stokes’ black G&L Tribute Fallout guitar and Pearces’ Goldtop ’78 Les Paul Deluxe guitar were in communion, not with a clear sanctioning or delegation of the “rhythm” guitar but rather playing off each other in pinging melodies. Pearce had some killer guitar solos as well, a combination of straight-up technical chops exhibited in a fluttering staccato picking hand and a slithering, bending right hand. He pressed into the high notes while gracefully staggering around the stage. Particular highlights were the legato “Whatever” solo and the solo of the encore’s “I’m Not Getting Excited.”

The band established a warm rapport from the get-go. There was a big, inflated (or stuffed??) half of a fish displayed vertically onstage as per their latest album cover, as if emerging from the stage and swimming up into the smoky lights above, yellow eyes staring into the audience–but in a friendly way. At one point, they challenged the audience to come up with a name for it. Pearce praised us when we finally came up with “Sidney Fish” (Sidney Gish’s long-lost cousin, perhaps). In another interlude, the bassist, Benjamin Sinclair made an extended plug for his tour blog, “Breakfast and Travel Updates.” They invited any crowd members to follow it “if you need stability in life,” because Sinclair posts every day, or to email breakfastandtravelipdates@breakfastandtravelupdates.com if you just need “life advice.”

Given the audacious lyrics of some of The Beths’ songs, I was surprised by how modest and almost shy Stokes was. She came in with a white dining hall-esque mug from which she sipped throughout, and seemed to embody that personality, if not for her unflinchingly honest vocals and roaring guitar. Her stage presence was humble and friendly, but stunningly intense, closing her eyes in stillness as she traversed the octave and emotional ranges of her songs. In an era when alleged authenticity is fetishized, the lack of naturalness in the stage presence only added to the experience. Much like with the self-proclaimed “nerdy” way they approach music, Stokes was transparent and friendly on stage, at one point chastising herself for going through her interlude “bits'' too early on: “You really need to save some of your bits for later in the set. Take my advice.”

The vocals sat quite quiet in the mix, which was a bit disappointing at times, but also only seemed to add to the experience at other times, putting more emphasis on the collectivity rather than a single narrator. The band resisted this hierarchical tendency.

In the midst of the more punk-oriented sound, songs like “You Are A Beam of Light” stood out, a soft fingerstyle reflection amongst the slew of heavier rock songs. Stokes’ right thumb on the low E string set a constant pulse for the song, as her other fingers rippled through transforming chords with a skill that called to mind her classical training. The vocals were more audible without all the noise, and the harmonies took center stage in all their glory. The richness of the vocals, even without the strums and drums, fleshed out the song into a full-bodied, thrumming piece. “You Are A Beam of Light,” from their 2020 album Jump Rope Gazers was The Beths’ “first attempt at an ‘acoustic’ song,” as Stokes humbly framed it–but the palpable chills amongst audience members calls this novice narrative into question (DIY Mag). Although this song still has The Beths’ determinedly optimistic tint (“You are a beam of light, Maybe that’s why your battery runs dry”), this time it feels more like a desperate attempt to justify the painful suffering of a friend–a positive tone for survival’s sake, bearing a melancholy perfume that can be ignored but not completely filtered away. The lyrics felt post-apocalyptically intimate, or rather, contemporary:

I hear you cry

From the other side

Of a broadband line

That cuts out and in, two seconds behind

You go quiet and say goodnight

From the other side

Of a broadband line

That cuts out and in, two seconds behind

You go quiet and say goodnight

There are some angsty, reckless lyrics (“I will go out tonight, I’m gonna drink the whole town dry, put poison in my wine, and hope that you’re the one who dies” or “I wanna crash the car and hit the water” or “You wouldn’t like me if you knew what was inside of me”).

These lyrics sound sort of “teenage,” actually, which was why I was surprised the band members were over a decade past their teenage years. But there is a reason for this. When The Beths’ were beginning to write much of their core content, Stokes had just broken up with her partner of eight years–which means it was a relationship that had started in her teens and lasted into when she was a twenty-something. Then recently during the COVID lockdowns, Stokes revisited this: “needed something to kick me into gear…I felt numb to what was happening around me. So I began digging through old journals, tapping back into old emotions. That means some of these songs are very ‘2021’ and some of these songs place me in 2015, emotionally” (Relix). Their latest album, Expert In A Dying Field references this “second adolescence” of warped time: As Stokes states in her title track, “Love is learned over time, ’til you’re an expert in a dying field.” Thus, The Beths was formed in the aftermath of a breakup which was causing Stokes go through “a second adolescence, on my own for really the first time” (Relix). The “adult break-up album” sometimes gets a bad reputation, but The Beths do it well (The Flood).

Although the music may have “adolescent qualities,” the beauty of second adolescence is that it inevitably does give more perspective. The fact that The Beths is a bit of an older band–early 30s, but still older sibling vibes compared to the “sexy babies” that populate a lot of the contemporary music scene today–does influence the music. The fast, pop punk songs with sad lyrics that have become increasingly popular recently (e.g. Olivia Rodrigo) but with a harder, more instrumental spin. But also another layer of contrast–if you peel away the upbeat sound and the sad “meaning” beneath that, there is actually a core of optimism and good-natured selflessness. They don’t get carried away with sadness in the way where it becomes extreme self-absorption, victimhood, or self-fetishization into an aesthetic, or even self awareness to the point of cynical paralysis.

Their songs reflect their maturity and growth. As Pearce said in an interview, “There’s only so many times you can write that fast, self-loathing banger…How many of those are in the back catalog now? It’s like, OK, we’ve gotta find some other emotions to put into the music. [Like] love songs that say ‘I love you’, without also saying ‘but I hate myself.’” I don't add The Beths to my “sad” and “happy” playlists that somewhat toxicly draw me deeper to these extreme emotions. Rather, I can experience fullness in most any single The Beths song.

The Beths feel emotions, but they feel a full range of them, even within one moment. There is this concentration situated within the broader context. Rolling Stone’s assessment of The Beths as “self deprecating power pop” seems derogatory. But I love this self deprecation because it's so decidedly not a self-flagellation that prevents growth. It talks about feeling bad but in a human way, not in a pathological or narcissistic way (making the world drop at their feet because oh they suffer the most) not overly making it all about them. Stokes sings about her emotions matter of factly–expressing their intensity without losing sight of the broader world. Listening to The Beths feels like processing emotions vicariously in a healthy way, like eating a delicious plate of spinach. There’s also something about watching The Beths that’s a bit comforting, like a cool older sibling, or a more mature version of myself. Someone who might still hate me at times but who hates me a bit less. And often, that can honestly feel like the best case scenario.

Stokes is a wonderful lyricist, and there are plenty of words on the album, but they’re the type of band where you don’t have to hang onto every word. It feels like there’s not that intuition, and it's not instinctual.

The way I find myself listening to most of The Beths lyrics is letting the words wash over me in a delicious tumble of New Zealand-intoned syllables, where certain words or phrases catch on if their meaning is magnetic to me. “Future Me Hates Me” is one great example–it initially stuck to me because I (somewhat stupidly??) pictured a milkshake where Stokes said “cold shakes'' and latched onto that without understanding much.

The literary arts major in me (sorry) couldn’t help but appreciate how some of the song titles are also somewhat perplexing diptychs of words like “Best Left” where you can’t immediately piece together what the subject-object combination is or delineate what's the noun, so they become somewhat solid formal objects. The lyrics wash over me in a delicious tumble of New Zealand-intoned syllables. Not all of the meaning is immediately apparent, nor is it riddled with intense pop culture references that a lot of today’s indie music is. It's metaphorical at times, but also beautifully literal. It feels like a choose your own adventure experience listening to it–there’s just so much going on. In the best of ways. It doesn’t feel overwhelming, it feels spacious enough, like I've walked into a bountiful pantry and can sit on the countertop eating whatever I desire, letting my eyes roam over the fruits, carving out a space for myself within it all. And by the end of the three minutes (their songs are pretty tight) it always feels like a full course, no matter what I was munching down on.

The Beths’ songs lend themselves to relating in many ways. For example, Stokes says “Future Me Hates Me” was about the ultimately excited anxiety of leaping into things that you think future you might regret. Stokes says the song is “not about future you looking back and hating you–it’s about present you being worried about what’s gonna happen down the road…I don’t think of it as being pessimistic. I think of that song as being an optimistic song” (Since I Left You). But in high school, I understood the song as a purely hateful anthem where a future version of myself will always unequivocally hate those past versions, such as my aversion to my old identities and the people from my town who I didn’t feel understood by and was eager to leave. A very “adolescent” reading, to be sure, but now I can appreciate it from a different way. This second adolescence inevitably comes with the nuanced perspective of more experience–it’s not a repetition but rather a reprise. And if Stokes truly is singing this as a future self looking back at the old Liz and hating her, she’s doing it while grinning–a sympathetic laugh while shaking your head.

Just as the content was dealing with seemingly adolescent feelings in a nuanced way, The Beths’ sound also reflects this callback. The music is a bit more of a traditional brand of rock, displaying a “Hey, look at this interesting thing I can do with my guitar” technical prowess, not “cool” songs, not trying to be “trendy” but more a “studied” perspective. The Beths have yet to go viral on TikTok; there isn’t really that TikTok cue point in a lot of songs. People aren’t commenting on their youtube videos things like: “it’s at 2:14, thank me later,” and you don't have to scrub backwards over and over in the songs to get to that one sweet spot. The songs are more generous than that TikTok crux. The dopamine release is distributed a bit more evenly throughout the song. The Beths showcase the music without the influencer aesthetic package. Ignoring the trends, not even in a self consciously subversive way but an authentic way.

It’s fitting, then, that in an interview, The Beths mentioned a game they play to pass time on the road which demonstrates this tendency to appreciate slowness, called “baker's dozen,” where they listen to a song thirteen times in a row.

The Beths are unabashed in the way their music isn’t necessarily what’s cool or trendy or current right now. In an interview, Stokes said, “I call us a guitar-rock band because I think it’s quite funny—sometimes it feels like period music… But it’s a palate that we just love. I don’t feel hemmed in by rock-and-roll. We could make whatever music we wanted to, but this is what we enjoy.” Their songs are tight, and usually have a guitar solo following the third chorus. But come on now! Who doesn’t love a guitar solo following the third chorus? The Beths’ adherence to their own certain formula points towards developing something to the fullest. Adherence to musical conventions doesn’t mean they're not complicated or amazing, just like something that doesn’t fit the tradition is automatically of higher value. Stokes and Pearce knew each other from high school and the band formed at music school where they studied jazz, Stokes–trumpet, and Pearce–piano. Stokes “loved learning about music, but I missed lyrics… I was communicating in melody and improvisation, learning a lot of repertoire. I was missing songs, and being able to express myself that way. I was nostalgically missing the guitar music that I grew up on. I was like, ‘I’m going to start a rock band.’ Maybe Jonathan was a little more dissatisfied with studying.”

But they still apply the “discipline” of studying to rock-and-roll. “Liz and I really connect over rejecting the ego of alternative music where people are trying to do clever things, or cerebral things. I think Liz and I look for the things that work. The devices that really get the job done and get the heart racing and make the climactic moments happen.” Their studying of musical devices definitely shows. I was uncontrollably wrought with jolts and closed eyes as their syncopated vocals and changing tempos hit hard among the cascading four-part harmonies.

Because The Beths’ music is not as much fixated on the current trend but subscribing to a varied and nuanced multiplicity both instrumentally and lyrically, everyone at the concert, dads and they/thems alike, seemed to resonate. Just like the collective musical elements in The Beths’ music, the concert experience was a collective one as well. This led to a concert that felt like a collective experience with an actively shared camaraderie, in contrast to some of the big-venued, aggressively hyped and ultimately alienating concerts that I’ve experienced.

This crowd was by far the friendliest of any concert I’ve gone to. It matched The Beths’ utter genuineness; even though we were grimacing and yelling along in passion, we took turns at who got to be gripping the stage. The girl next to me sang to the band with a beautiful desperation that made me smile. Other fans included a trio of barista coworkers who were sharing (positive) opinions on the new hire, who were bonding with a birdwatching girl who worked on a farm lamenting the fact that they all had to get up early. Another conversation nearby was intergenerational, discussing the gentrification of Cambridge and Somerville over the past decades.

The crowd gelled throughout. We were jumping for the dreamy “Jump Rope Gazers,” and got especially excited for one of the encore songs, “I’m Not Getting Excited” as the suspenseful eighth notes fizzed into a crescendo. And as Sinclair referenced in his blogpost, someone held up a Zippo lighter for the slower fingerstyle “You Are a Beam of Light.” In the song “Whatever,” the collective rumbling chant of the audience shouting the background “whatever yeah, whatever!” drowning out the backing vocals of the real band, but not in an obnoxious performative way, but rather a call and response way with the band. The angst was palpable, and it felt like real interplay. In the crackling Little Death, there was a dynamic interplay between performer and audience where the crowd shouted “YOU SAID, YOU SAID,” and “I’D DIE, I’D DIE.” I enjoyed how this added to the syncopation, emphasizing the words in a different way than you can get from any by definition static studio recording. It felt like a new thing we were creating. This felt especially true in songs like “Silence Is Golden” when the audience chanted the namesake phrase several times–we created a huge song together but also a stillness within it. (Were we singing in a New Zealand accent? I don’t know…)

The sense of a warm collective is important to the band. Elizabeth Stokes, the band's frontwoman, once said they were influenced by “band[s] like Wilco where you see how much the fans love being Wilco fans”. Stokes added, “we’re playing to the cheap seats. We’re a live band, playing rock instruments. We wanna be direct.” This is another thing the sonic elements are responsible for, because this fan relationship isn’t always the case. The Beths are a big contrast to recent notorious viral concerts such as Steve Lacy or Ice Spice where people vie for the best spot at concerts only to know one line of the songs.

The power of participatory art in the live concert felt inspiring to me in the context of the social movements and revolutionary battles we face today. “Doing” rather than consuming culture is an important part of identity and social movements, and I think I feel that at events like live concerts in venues like The Sinclair where we can come together. As Amilcar Cabral said, culture by definition lends itself to action, as culture is “vigorous manifestation on the ideological… plane.”

Most collective identities are relationships rather than stable traits. Collective identity hinges on communication which is a kind of “joint action”; this communication forms the community (Taiwo 40). As theorist Olufemi Taiwo says, “we have to share to communicate” (Taiwo 40). Collective identity is a contribution toward a “we.” Reciprocity is key. Emotion rather than information is a key part of collective identity. Melucci points out that “there is no cognition without feeling and no meaning without emotion.” After all, we say collective body for a reason!

Like most collective experiences, this one had enduring effects. By the end of it, group photos were taken of people who had been standing near each other, names exchanged, and group chats were formed between girls from various colleges in New England who’d traveled alone to see the band.

A couple of weeks ago, I turned twenty and kissed my teenage years goodbye. I’m not reluctant to leave my adolescence or yearning to remain stagnant in time. But I’m not dying to get older and over it, either. I don’t think adolescence is bad and don’t believe in the idea of constant capitalist-informed cult of self-improvement (New Year's resolutions, career ladders, and abandoning innocence for a crutch of justifying complicity with a jaded, cynical air of “I know how it really is''). At the end of the day, adolescence is a construct, and I’m flowing through what I'm flowing through; there is no right trajectory in this nonlinear existence.

The next morning, even though I walked up from the train station in last night’s clothes, smudged makeup, and very little sleep, arriving at Memorial Hill just in time for studio, future me didn’t hate me for it.

Tap into the collective experience of the concert by listening to a Spotify playlist of the setlist from the concert:

Photography by Saraphina Forman